The Panama Papers and the Correlates of Hidden Activity- Unless you’ve been livipanama papers Aljazeerang under a rock in the British Virgin Islands, you might have heard of the massive leak of documents from Mossack Fonseca, a Panamanian law firm whose services included helping its clients create shell corporations and store their assets in offshore tax havens.

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and their affiliates recently began releasing juicy details on politicians and other people in positions of power who appear to have been using the firm to manage their offshore finances.

The Irish Times and the ICIJ were kind enough to share with me some initial aggregate data on the number of intermediary companies, clients, and beneficiaries named in the leak which can be tied to a given jurisdiction by address. The result is a rough mapping of the countries linked to Mossack Fonseca throughout its forty year history in the offshore business.

In addition to a torrent of political scandals and crises, the leak has resulted in a renewed rallying cry to reform the international tax system. But aside from the political implications, the Panama Papers have the potential to help us better understand two things:

- What kinds of countries do these offshore firms do business with?

- Are the tools we use for determining the relative risks of hidden cash any good?

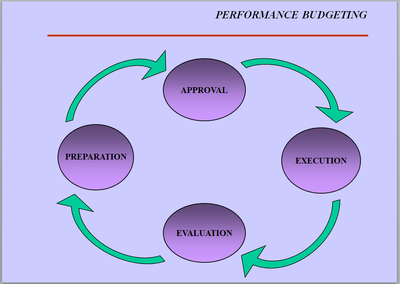

I wanted to see if popular measures of financial secrecy, money laundering risk, and corruption that development policymakers, advocacy organizations, and regulators rely on were any good at predicting the number of business relationships with Mossack Fonseca. First controlling for average income and total population size, I looked at correlations between these indicators and the total number of companies, clients, and beneficiaries that appeared in the Panama Papers (the results are the same looking at each type of entity separately).

The short answer is that some indicators – specifically those focused on secrecy – are actually pretty good predictors of which countries are likely to do business with a dodgy law firm that specializes in offshore finance. The graph below shows the results across all the indicators that I tested. All indicators have been transformed so a higher value is a “worse” outcome, such as a higher risk of money laundering or corruption. Each point shows the change in the log value of total links to Mossack Fonseca for a one unit change in the indicator, controlling for per capita GDP and the country’s population.

Measures of financial secrecy predict actual financial secrecy.

One of the most reliable predictors of a country’s dealings with Mossack Fonseca is how it scores on the Financial Secrecy Index (produced of former-CGD taxation guru Alex Cobham) which is used to assess the risk that a jurisdiction is used to hide a significant share of money in the global economy. A 10% increase in a country’s FSI is associated with an approximately equivalent increase in the number of entities from that country named in the Panama Papers. A one standard deviation increase in the FSI – roughly equivalent from moving from Norway to Jersey – leads to about a 90% increase in the the number of entities. Other measures carry less predictive power: there is no obvious relationship between an index of Financial Transparency and Standards produced by theBasel Institute on Governance and the number of links.

Read more: Matt Collin – CGD

Photo credit: [Thomas Trutschel/Photothek via Getty Images] via Aljazeera